Everything you need to know before you go — history, etiquette, where to see them, and what NOT to do.

Introduction

Kyoto changes when the sun goes down.

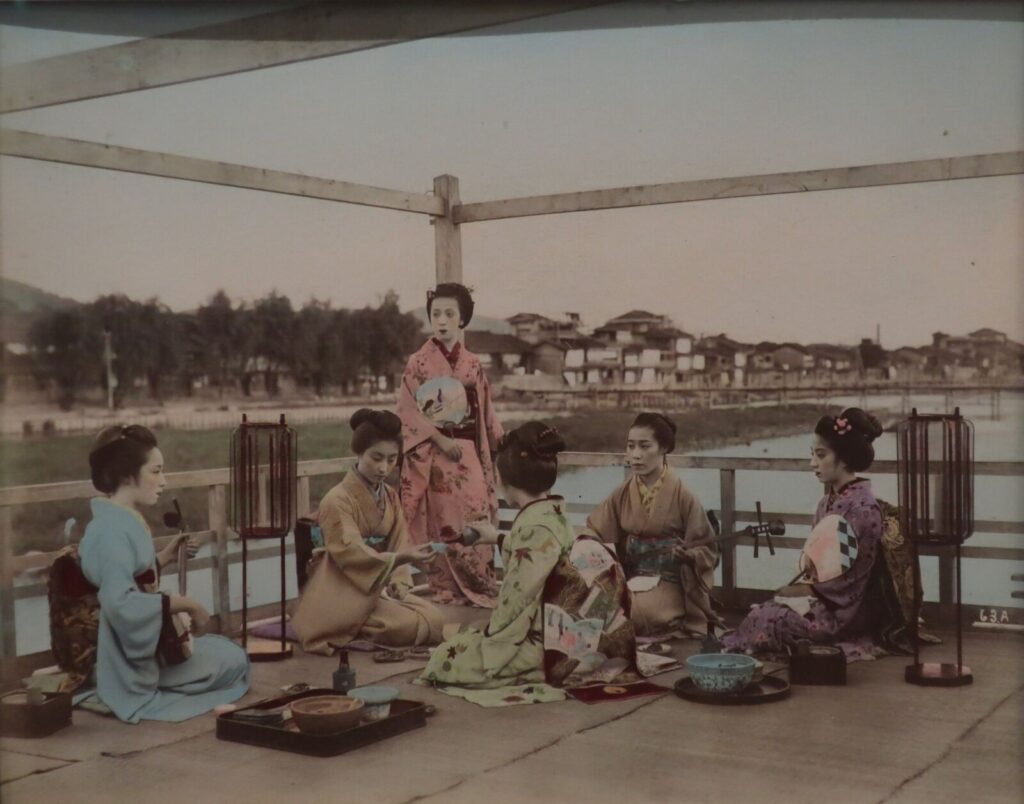

The geisha districts awaken as the day slips into evening. In the hanamachi, lanterns warm the alleys and the familiar click of geta shoes marks the start of the evening’s quiet choreography. Somewhere behind a latticed window, a shamisen welcomes the dusk. In the glow of a passing lantern, a geisha slips into an ochaya, the night folding closed behind her — a brief silhouette in silk, here and gone.

The floating world awaits.

These hanamachi — “flower towns” — live in the space between the ordinary and the sublime, a remnant of the old ukiyo, the floating world. They are real, working neighborhoods, yet brushed with a kind of elegance that still catches visitors off guard. The geisha and maiko are the flowers of these streets: trained, disciplined, rooted in tradition, and far more human than the myths suggest.

But for many travelers, Kyoto’s geisha culture is confusing. What’s the real difference between geisha and maiko? Where can you see them without crossing boundaries? And which stories online are genuine — and which are fairy tales dressed up as fact?

This guide strips away the guesswork. You’ll learn how the hanamachi function today, how to recognize geisha and maiko with confidence, and how to appreciate their world with clarity and respect. Think of this as your grounded entry into a tradition that’s often misunderstood — but never boring.

Quick summary

- Geisha & maiko are trained performing artists and hosts, not escorts.

- Peak pre-war geisha numbers reached tens of thousands nationwide (often cited as ~80,000 in the 1920s).

- Today only around a thousand remain across Japan, with roughly 200–300 active geisha & maiko in Kyoto (district counts fluctuate year-to-year).

- The safest, most respectful ways to see geisha are official performances, seasonal odori (dance) events, licensed tea-ceremony experiences, and special public events (not street-chasing).

What Is a Geisha?

Geisha are highly trained performing artists specializing in traditional dance, music, conversation, and hospitality. In Kyoto, they are known as geiko, and their apprentices are maiko.

What geisha are:

- Professional entertainers trained in dance, shamisen, singing, tea ceremony, and hosting

- Cultural custodians preserving centuries-old Kyoto arts

- Full-time artists who perform at private banquets and seasonal events

What geisha are NOT:

- Escorts

- Public performers available for casual photos

- Characters from movies or staged photo shoots

- A relic — Kyoto’s geiko and maiko are active modern professionals

Their true role is to preserve refined arts and host guests with skill, elegance, and deep cultural knowledge.

The History of Geisha

Kyoto’s geisha culture traces its roots to the streets leading to Yasaka Shrine, where pilgrims once stopped for tea, rest, and entertainment. Over time, women who excelled in dance and music formed guilds to train and protect one another.

Key points:

- Early entertainers in Japan were male (known as taikomochi).

- Female geisha emerged in the mid-1700s.

- By the early 1900s, there were over 80,000 geisha across Japan.

- Today, Kyoto remains the most renowned center, with around 200–250 geiko and maiko.

The geisha world has endured fires, wars, cultural shifts, and tourist waves — yet it continues because the arts remain alive, relevant, and supported by locals.

Kyoto’s Five Hanamachi (Geisha Districts)

1. Gion Kobu

- Largest, most famous, home of Miyako Odori

- Wide range of dance traditions, very traditional atmosphere

- Beautiful tea houses around Hanamikoji Street

2. Gion Higashi

- Smaller and quieter

- Known for strong dance training and refined, minimalist aesthetics

3. Pontocho

- Narrow lantern-lit alley along the Kamo River

- Known for elegant dance and refined summer kawayuka dining

4. Miyagawacho

- Historically linked to Kabuki theatres

- Lively performance style, energetic dances

5. Kamishichiken

- Oldest hanamachi, near Kitano Tenmangu Shrine

- Traditionally calm, dignified, and home to the Plum Blossom Dance

These districts exist because geisha houses (okiya) and tea houses (ochaya) clustered together historically, forming tight cultural ecosystems.

Life Inside the Hanamachi

Young entrants typically apply to an okiya and begin as shikomi (house trainees), then debut as maiko after passing lessons and a formal misedashi ceremony. Over several years a maiko becomes a geiko.

Daily pattern (typical): morning lessons (dance, shamisen, tea), afternoon fittings/rehearsals, evening banquets/ozashiki, late-night return to the okiya; days off are relatively rare. A chalked lesson/schedule board (monthly keiko schedule) is still used in many districts to show who trains when — an old system still visible around training theatres.

Living arrangements: senior geiko may live independently; many apprentices (maiko) usually live in their okiya while training.

Geiko vs. Maiko: How to Tell the Difference

Geiko: subtler kimono & shorter obi, often wear wigs, lighter white makeup, simpler accessories and zori sandals.

Maiko: bright kimono, long darari-obi, elaborate seasonal hana-kanzashi hairpins, tall okobo sandals and stronger white makeup. Maiko hair is typically the woman’s natural hair (not a wig) and is dressed in distinctive styles.

These visual cues are the easiest way to tell them apart.

Seasonality: kimono motifs, kanzashi and accessories change with the season and festival calendar — almost all items are produced by specialized craftsmen.

What Geisha and Maiko Actually Do

- Perform classical dances at odori and private banquets.

- Play shamisen and other instruments, lead tea ceremonies, and guide refined conversation.

- Participate in festivals, shrine visits, and community rituals.

- All appointments and billing are handled through the ochaya or district office (kenban); geisha do not accept casual direct payment from random guests.

How To See or Meet a Geisha (the respectful ways)

1) Theatre performances (highly recommended & public):

- Gion Corner — daily condensed arts show (tea ceremony, kyogen, maiko dance) and very tourist-friendly.

- Miyako Odori (Gion Kobu) — April; major spring dance by Gion Kobu geiko/maiko.

- Kyo Odori (Miyagawacho) — spring.

- Kamogawa Odori (Pontocho) — May.

- Kitano Odori (Kamishichiken/Kitano) — late spring (Kitano Odori/Plum Blossom events).

- Gion Odori (Gion Higashi) — usually in autumn/November.

2) Tea-ceremony / cultural experiences:

Reputable cultural centers and licensed tea-ceremony venues sometimes arrange maiko demonstrations or short tea events. Book through trusted operators only (some are offered with theatre premium seats). We recommend: Kimono Tea Ceremony Maikoya however, for a slightly simpler option, we also recommend An Kyoto Japanese Culture experience.

3) Special public events / seasonal appearances:

- Hassaku (Aug 1) — Gion hanamachi visits to thank neighborhood merchants (a public “thank-you” walk/visit).

- Kamishichiken Beer Garden — summer beer garden in the Kaburenjō theatre garden where maiko/geiko serve and meet visitors (affordable, public).

- Setsubun — Yasaka shrine is ofen the main place to see Geisha during this February Festival.

4) Private banquets (ozashiki):

These are real private events that require an ochaya booking or a trusted intermediary (and can be costly — historically many tens of thousands of yen per guest). Avoid “one-click” geisha dinners sold by unknown sites; genuine arrangements go through established hanamachi channels.

Patronage, Payment & the Role of the Danna

How Payment Really Works

- Guests pay the ochaya, not the geiko.

- Bills are settled by the tea house at the end of the month.

- Patrons may cover kimono or training costs, but modern patronage is rare.

- Historically, a danna was a wealthy patron who supported a geiko’s artistic development.

- Today, this is uncommon and not romanticized — it is practical, financial, and tied to the preservation of the arts.

Etiquette for tourists — what to do and NOT do

Do

- Watch respectfully from a distance

- Move aside on narrow streets

- Support official theaters and experiences

- Learn basic etiquette—bow slightly and smile if you accidentally make eye contact

Don’t

- Chase or block them for photos

- Touch their kimono (yes, people do this…)

- Stand in front of them to force a selfie

- Follow them into private alleys

- Shout “geisha! geisha!”—especially in Gion; it’s considered rude

Kyoto has passed ordinances against disruptive behavior in Gion because of increasing problems with tourists.

Annual events & calendar

January: New Year rituals, shrine visits.

February: Setsubun dances.

April: Miyako Odori (Gion Kobu), Kitano Odori (Kamishichiken) — spring odori season.

May: Kamogawa Odori (Pontocho).

July–August: Gion Matsuri activities; Kamishichiken Beer Garden (summer beer garden; public).

August 1: Hassaku / neighborhood thank-you visits in Gion (maiko/geiko visit local merchants — public).

October / November: Autumn dances and Gion Odori (depending on district).

December – Koto Hajime: Ceremony marking the “beginning of the artistic year”. Also the Kaomise or "Face showing" event at Minamiza Theatre. (kind of like the Kyoto version of the Oscars)

Famous Geisha, Legends & Pop Culture

Mineko Iwasaki

Kyoto’s most internationally-known geiko; she published her autobiography Geisha: A Life (also published as Geisha of Gion / Geisha, A Life in English) to correct inaccuracies in Memoirs of a Geisha. She later married after leaving the okiya.

Yuki Kato (Morgan O-Yuki)

A Kyoto-born geisha who later married George Denison Morgan, a nephew of financier J. P. Morgan.

Pop Culture

The Makanai (recent Netflix series portraying hanamachi life)

Memoirs of a Geisha (fiction, loosely inspired)

A Note on Memoirs of a Geisha (and Why Many Geiko Dislike It)

Arthur Golden’s Memoirs of a Geisha shaped how many people outside Japan imagine geisha — but the book contains major inaccuracies.

The biggest criticism came from Iwasaki Mineko, one of Kyoto’s most accomplished geiko, who was interviewed for the novel under a confidentiality agreement. She later stated that Golden misrepresented her, revealed her name without permission, and portrayed geisha life with exaggerated drama and outright falsehoods.

Her main objections:

- Over-sexualization: The novel implies geisha are part of the sex trade — something she strongly refuted.

- Inaccurate training/lifestyle details: Several customs, hierarchies, and rituals are fictional.

- Sensationalized plotlines: Abuse, bidding for virginity, and forced competition were dramatized for storytelling, not reflective of Kyoto’s actual hanamachi.

Iwasaki later wrote her own memoir, Geisha, a Life, to correct the record and present geiko culture as she experienced it.

Key Kyoto Geisha Phrases

- Geiko (芸妓): Kyoto term for geisha

- Maiko (舞妓): Apprentice

- Okiya: Boarding house

- Ochaya: Tea house where banquets happen

- Onee-san: Senior mentor

- Okāsan: Mother/owner of the house

- Ookini: Thank you

- Ohana bakaite / Ohana bakate: Polite euphemism which means "I'm going to pick flowers" for “I need to use the restroom”

Where to Experience Geisha Culture

- Gion Corner – nightly arts showcase

- Kaburenjo Theatres – annual seasonal dances

- Kitano Tenmangu Shrine – plum festival appearances

- Yasaka Shrine – festival participation

- Licensed cultural centers – tea ceremonies, small performances

- Cultural museums – exhibitions on kimono, arts, and hanamachi life

Join Our Tours

This full-day journey weaves together Kyoto’s sacred landscapes and its quietly elegant hanamachi. As we make our way from the vermilion tunnels of Fushimi Inari to the heights of Kiyomizudera, the route carries us through lanes where maiko and geiko still hurry between evening appointments. It’s not a “geisha tour,” but it offers a genuine glimpse into the neighborhoods they call home — the lantern-lit alleys, the ochaya tucked behind wooden facades, and the atmosphere that defines Kyoto after dusk.

For a rare, intimate encounter with Kyoto’s geisha tradition, join our river cruise in Arashiyama led by Kohaku, a former maiko. As the boat drifts along the Katsura River, she shares stories from inside the hanamachi — the training, the artistry, the discipline, and the humanity behind the silk. It’s a peaceful, atmospheric experience that brings the world of geiko and maiko into focus, not through performance, but through personal insight and lived history. We will also visit the famous Bamboo forest, Tenryuji Temple, as well as the hidden gem Otagi Nenbutsuji.

Small Group

Sacred Stone and Flowing Silk: Arashiyama Temples, Bamboo Forests, and Maiko River Cruise

Final Thoughts: Stepping Back Into the Night

Kyoto’s hanamachi are small in scale but vast in meaning — places where tradition isn’t preserved behind glass but lived, practiced, and refined every evening. To understand geiko and maiko is to see past the surface: past the bright silk, past the lantern glow, past the myths that cling stubbornly to them.

Walk these streets with patience, and the floating world reveals itself in small flashes — the rustle of kimono, the hint of perfume on a passing breeze, the distant thread of a shamisen warming up for the night. It’s beauty you witness, not consume. Humanity, not mystique.

If this guide helps you navigate that world with clarity and respect, then you’re already doing better than most. Kyoto doesn’t ask you to understand everything at once — only to look, listen, and let the old rhythms of the hanamachi speak for themselves.

The night folds in, the lanterns glow, and the quiet choreography continues. The floating world awaits — gently, briefly, always just beyond reach.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are geisha real or mostly just for tourists today?

Geiko and maiko are absolutely real. Kyoto’s hanamachi remain active arts communities, and their work continues much as it has for generations — though modernized in small ways.

What’s the difference between a geiko and a maiko?

A maiko is an apprentice; a geiko is a fully trained artist. Maiko wear more colorful kimono and elaborate hairstyles, while geiko dress more simply and perform at a higher professional level.

Where can I see a geisha in Kyoto?

The best chance is in Gion, Miyagawacho, Pontocho, Kamishichiken, or Gion Higashi, usually around 5–6pm or 8–9pm when they move between engagements.

Is it okay to take photos of geisha on the street?

Only from a respectful distance — and never block their path, follow them, or use flash. Some streets in Gion even have fines for intrusive photography.

Can tourists meet a geisha?

Yes, but only through approved cultural experiences, performances, or venues like Gion Corner. Private banquets (ozashiki) require established connections and are not booked casually.

How much does it cost to hire a geisha?

Private ozashiki can cost from ¥150,000–¥300,000+, depending on performers, duration, and meal course. Public performances and shows are far more affordable.

Do geisha date or marry?

Geiko and maiko can marry, but doing so usually means retirement from the profession. Their training and schedules make relationships possible but challenging.

Are geisha entertainers or artists?

They are professional artists trained in dance, music, tea ceremony, poetry, refined conversation, and hospitality. Their work is closer to classical performance than nightlife entertainment.

How long does it take to become a geisha?

Training begins as a shikomi, then minarai, then maiko, then finally geiko. The entire path can take 5–6 years or more.

What should I NOT do in a geisha district?

Don’t block their path, touch kimono, take close-up photos, call out to them, stand in doorways, or chase after them. If you stay polite and give space, you’re good.

Are geisha prostitutes?

No. This misconception comes from postwar confusion and pop-culture myth. Geiko and maiko are professional performing artists, and their work centers on dance, music, refined conversation, and hosting — never anything sexual.

Can foreigners become geisha in Kyoto?

It’s extremely rare but not impossible. Kyoto’s hanamachi are very traditional, and most applicants grow up in Japan and start young. A few non-Japanese geiko have trained in other regions, but Kyoto maintains stricter requirements.

What happens if a maiko doesn’t become a geiko?

f a maiko chooses not to continue, she simply leaves the okiya and returns to regular life — no stigma, no “failure.” The house absorbs most training costs, and many former maiko go on to careers in hospitality, arts, fashion, or completely unrelated fields. Some stay connected to traditional arts; a few even return later as adult trainees.

What happens when a geiko retires?

Most retired geiko stay in Kyoto and continue teaching dance, tea ceremony, or etiquette within the hanamachi. Some run small businesses — kimono shops, restaurants, cultural studios — or become mentors to younger performers. Retirement isn’t an ending so much as a shift from performing to preserving the tradition.