Japan Sake Guide: Regions & Essential Info

More properly referred to as ‘nihonshu’, sake plays a fundamental role in the cultural fabric of Japan. With a heritage stretching back around two thousand years, production of sake is now an artform, the exploration of which leads you into an indulgent world. It may take a lifetime to master but you’ll enjoy every step on that journey. On this page you will find the following information:

— Japanese Sake: An Introduction

— Understanding %: It’s All About the Rice

— Wine & Dine in Nagano: Book a Tour or Charter

The popularity of sake is booming internationally and aficionados of the drink will find many excellent breweries to sample and buy from throughout Japan. For those taking their first taste of this indulgent world, the brewing process and terminology of sake can at first seem daunting. But armed with some basic information and a couple of key phrases, visitors can quickly start to understand the world of sake, how to choose one and most importantly, the cuisine to match it with.

Based in Nagano, we are the region’s No.1 tour and charter operator and a registered travel agent. We are proud to call Nagano our home for many reasons, but not least that it ranks among Japan’s largest and best sake and wine producers. We operate all year round and offer tours, transport, accommodation and more including visits to the finest local sake breweries, wineries and restaurants. We hope that we can entice you to visit.

JAPANESE SAKE: AN INTRODUCTION

Whether you have visit Japan or not, it’s likely that you have of and perhaps tried ‘sake’. Made from rice and water and multi-stage fermentation, sake is a brewed alcoholic drink that is widely consumed across Japan, with an estimated 1500 breweries spread throughout the country. For first-time visitors to Japan, it’s important to note that the world ‘sake’ – ‘酒‘ – actually refers to all alcohol including beer, wine and spirits. What most foreigners call sake is known as ‘nihonshu’ – 日本酒 – or ‘seishu’- 清酒 – translating as ‘Japanese alcohol’ and ‘refined/processed alcohol’ respectively.

The method of brewing alcohol from rice grain was brought from China around 2,000 years ago, and since that time refined to a point that ‘sake’ or better said, ‘nihonshu’ is a distinctly Japanese product that pervades the national culture, from family homes, social gatherings, business meetings to official functions of state and religious ceremonies.

Most sakes range from 12% to 17% alcohol (up to around 21% at its strongest) with a broad range of taste, such as dry and sweet, that will be easy for anyone to recognise and appreciate. Many are delicate and brewed to pair with local cuisine while others are raw and ready to go all by themselves. Brewing mostly occurs in the winter months of winter to February, taking advantage of new rice harvested in autumn and the lower winter temperatures that help control the fermentation process. Most sake is pasteurised – at least once, often twice – during the brewing process and for that reason will not improve over time, with a recommendation that most are consumed within 6 to 12 months; while also noting that both ‘namazake’ (unpasteurised sake) and ‘koshu’ (aged sake) exist and only add to the breath and complexity of this indulgent world. In order to enjoy sake while in Japan it’s worth familiarising yourself with its characteristics and the basics of brewing, and to do just that, it’s most important to start with:

UNDERSTANDING %: IT’S ALL ABOUT THE RICE

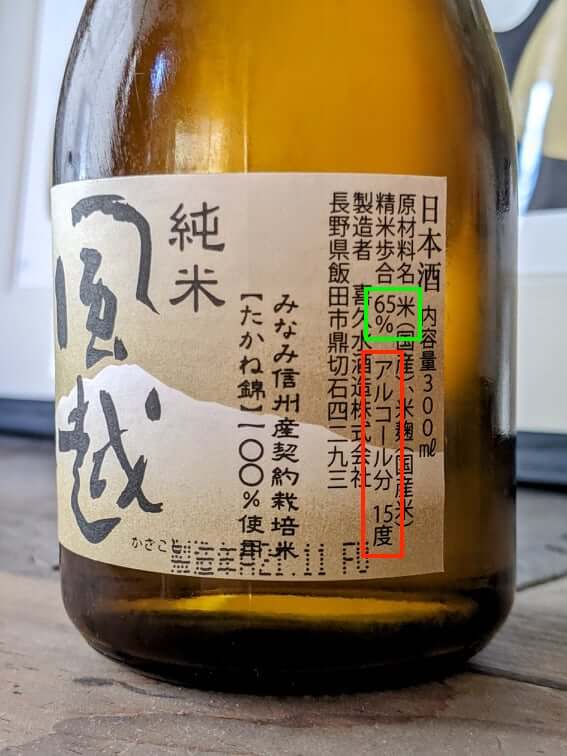

There is a common misconception about sake that it is more alcoholic than it is. It is a misconception that can be easily explained and just as easily resolved. In order to sell their sake, brewers must meet certain standards and list specific information on the label of all bottles including the percentage of rice and alcohol content. As explained under ‘The Brewing Process’ below, the first stage of processing sake is to ‘polish’ or ‘mill’ the rice grain. This involves stripping the raw grain, called ‘genmai’, of its outer husk and layers. This is done to remove poor tasting fats and minerals that spoil the overall quality of the sake. The percentage to which the rice has been polished – the ‘rice polishing rate’ – must be displayed on the bottle and will be shown as a percentage, typically somewhere between 70% to around 23% (at its lowest). Understandably, when looking at a bottle this percentage catches many peoples’ eye and they understandably think it is the alcohol percentage. It is not.

When you read 65%, it simply means that 65% of the grain remained and 35% had been removed following polishing (as indicated in the green box on the bottle above); or if you were to read 40%, it means 40% remains and 60% has been removed. In theory, as the percentage goes down, the taste becomes more refined but is just that – just a matter of taste. Some people prefer a higher percentage and the taste that comes with it while other prefer the lower end of the spectrum. This is where a couple of key terms come in that are worth remembering:

1 / HONJOZO: polishing rate of 70% or less (down to 61%)

2 / GINJO: polishing rate of 60% or less (down to 51%)

3 / DAIJINGO: polishing rate of 50% or less (down to around 23%)

There’s plenty of other terms to remember but these three are a good place to get started. In terms of alcohol, once brewed sake typically has an alcohol content of 17% to 20%. Most brewers dilute the sake with water reducing the overall alcohol content of most sake to between 12% to 16%, however there’s lots of variation including a type of sake called ‘genshu’ that is not diluted and will however a higher alcohol content. Alcohol content is not marked with a % symbol on the bottle however it must be included on the label. Look for these characters – アルコール (alcohol) – followed by a number i.e. アルコール15度 = 15% alcohol content (as indicated in the red box on the bottle above).

THE BREWING PROCESS

Much like beer and wine, sake is produced through a fermentation process. The entire process from start to finish typically takes around 3 to 5 weeks, with most sake then stored for a period of anywhere from 3 to 12 months to allow the flavour to settle and the process completed before it is ready to be consumed. Production of sake requires four key ingredients: rice, water, koij (a type of mold) and yeast, with the process of molding and fermentation taking place at the same time in what is referred to as ‘multiple parallel fermentation’. This multi-stage fermentation is required in order to convert the starch in the rice to glucose which can then be converted into alcohol, unlike wine for example which takes advantage of the sugars already present in grapes. Here’s a brief and very general overview of the brewing process:

1 / POLISHING or MILLING THE RICE: the first step is to polish or mill the rice grain to remove the outer husk. The husk and outer areas of the grain contain fats and minerals that are considered to be poor taste. By removing them, the taste of the sake will be better at the end and in theory, the more you remove, the better the state will be – as explained above.

2 / WASHING & SOAKING: the milled rice is then washed to remove any remaining bran and soaked in water – typically for 1 to 3 hours – until it has absorbed 30% of its weight in water and to prepare it for the next stage.

3 / STEAMING: the rice is steamed 40 to 60 minutes. This process begins to breakdown the starch inside the rice in preparation for fermentation. Once steamed, the rice is divided with some transferred to the fermentation vat while some is set aside to create ‘koji’

4 / ‘KOJI’ PREPARATION: steamed rice is inoculated with ‘koji’ fungi to create ‘kome-koji’ (koji rice). It takes around 2 days for the spores to cover the rice. As the koji-fungi grows, it produces enzymes that will power the fermentation process.

5 / STARTER MASH PREPARATION: yeast – or ‘kobo’ in Japanese – is combined with steamed rice, water and a portion of koji to create the ‘starter mash’. Known as ‘shubo’ in Japanese, the mash is highly-acidic and will suppress microbes that can spoil the sake. At this stage, everything is ready to combine and begin the fermentation process.

6 / FERMENTATION: standard ratio of steamed rice, koji and water are combined in a fermentation tank, typically over a 4-day period. Not everything goes in at once but is incrementally added and the temperature controlled and gradually reduced overtime. Known as the ‘moromi’ (main mash), the enzymes in the koji dissolve the starch in the rice into glucose and yeast converts those sugars into alcohol. The process typically takes 3 to 4 weeks and produces alcohol content around 17% to 20%.

7 / PRESSING: the ‘moromi’ is then removed from the fermentation vat and pressed by machine or hand, separating the alcoholic liquid from the lees – called ‘sakekasu’ in Japanese it is highly-nutritious and used for many things in Japanese kitchens. At this stage the alcoholic liquid is cloudy with rice sediments still present.

8 / FILTERING: most but not all sake is then filtered to remove sediments, resulting in a clear alcoholic liquid.

9 / FIRST PASTEURISATION: most but not all sake is then pasteurised at a temperature of 60 to 60°C in order to sterilise the liquid and make the enzymes in active. Some sakes, called ‘namazake’ are not pasteurized. This have a distinctly different tastes and notably shorter shelf life as the active enzymes will eventually ruin the taste i.e. they must be consumed within a short time of production.

10 / MATURATION: the pasteurisation process alters the aroma and taste of the sake requiring a period of maturation in which the sake is stored and left to settle. This can span anywhere from 3 to 12 months.

11 / BLENDING: water is typically, but not always, added to dilute the alcohol content from 17% to 20% down to 12% to 16%. Distilled alcohol can also be added at this time should the brewer wish to.

12 / SECOND PASTEURISATION: many brewers will then pasteurise their sake for a second time without any further storage or maturation.

13 / BOTTLING & DISTRIBUTION: that’s it, the sake is now ready to go! It is bottled, sold and consumed.

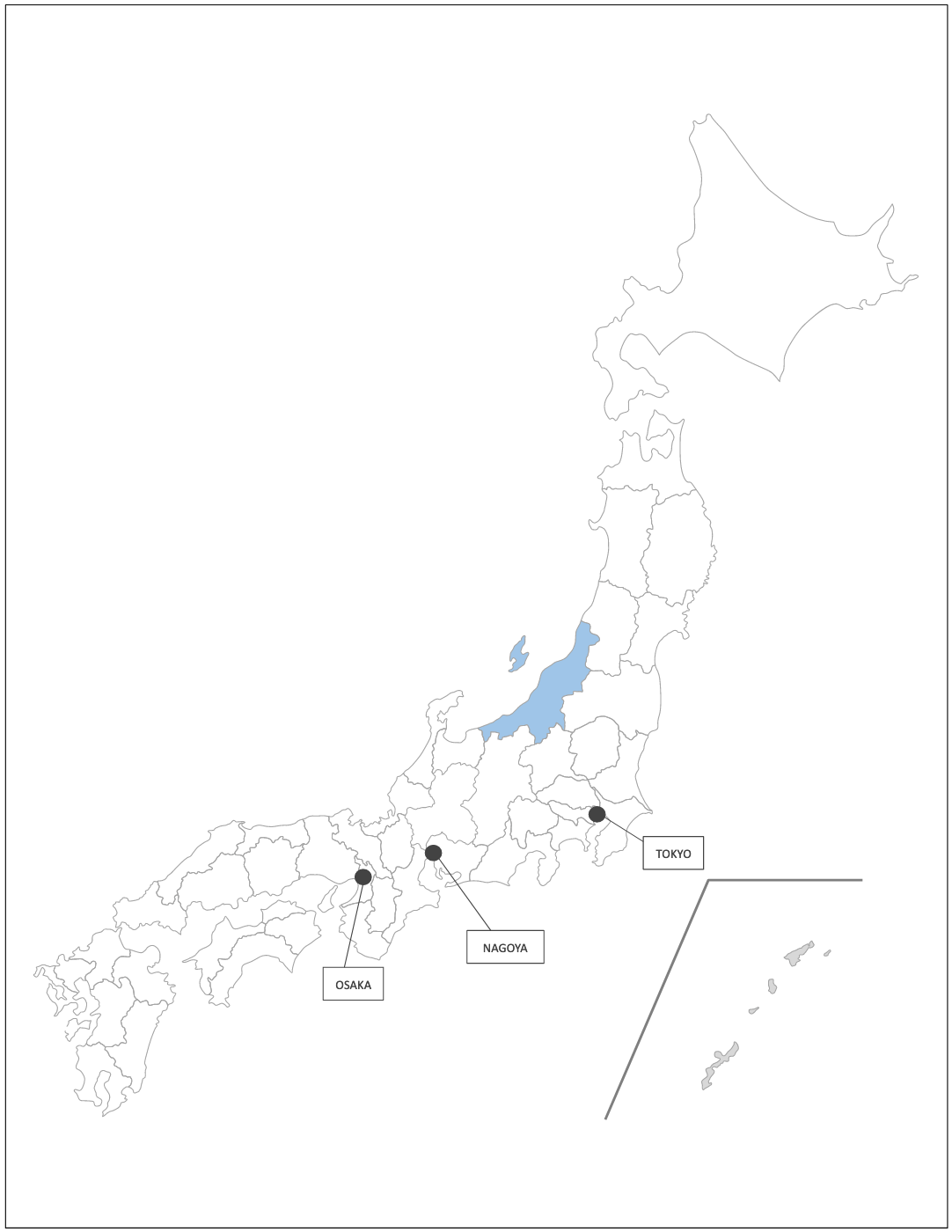

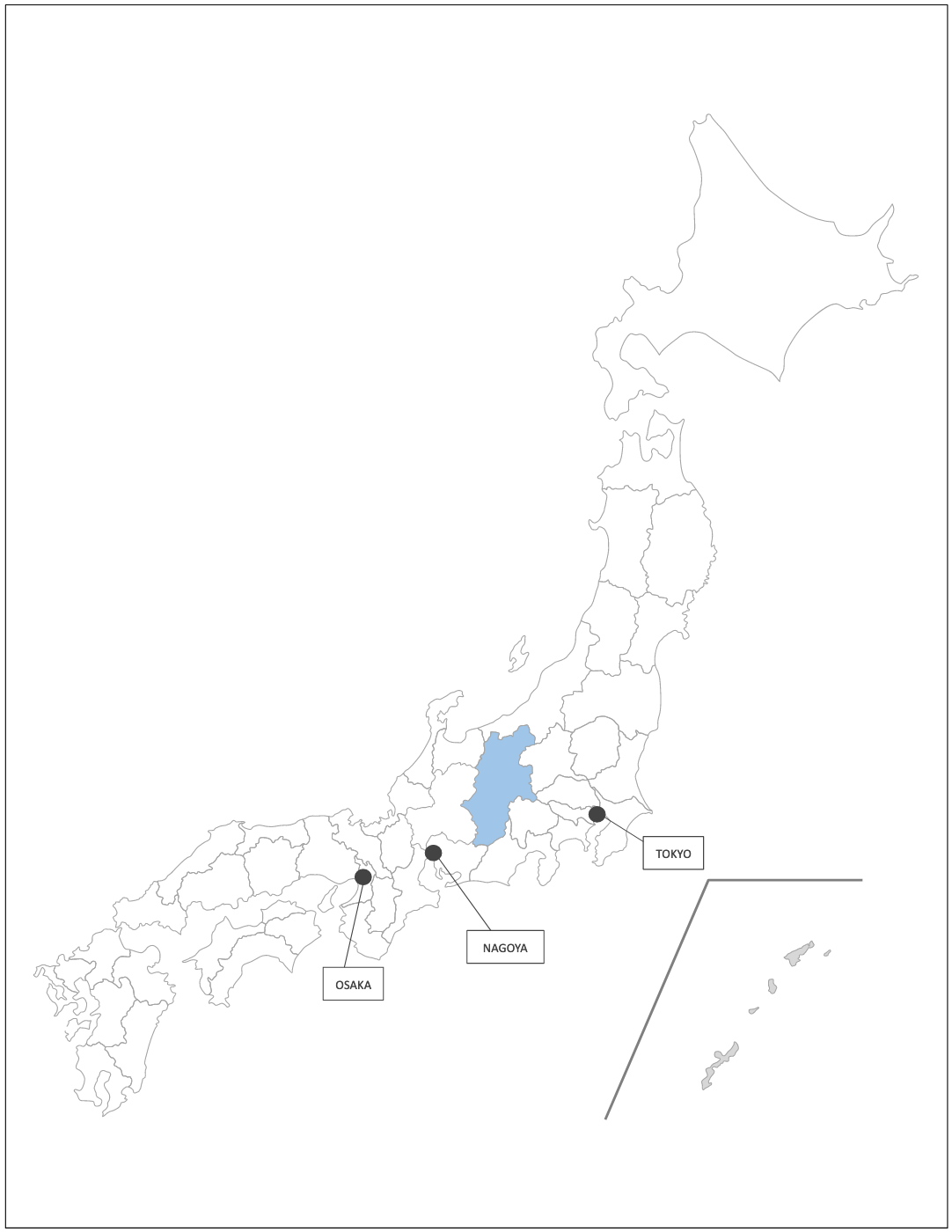

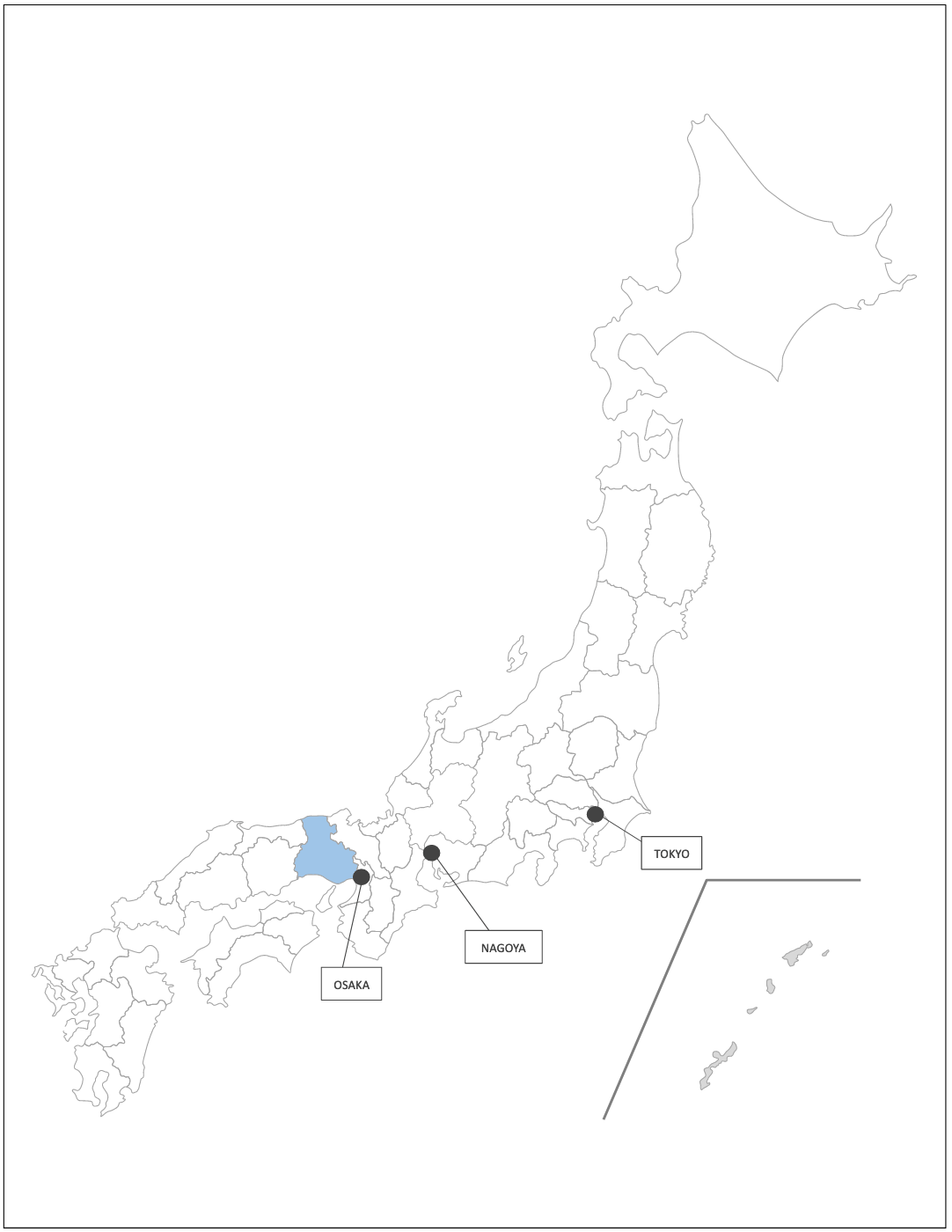

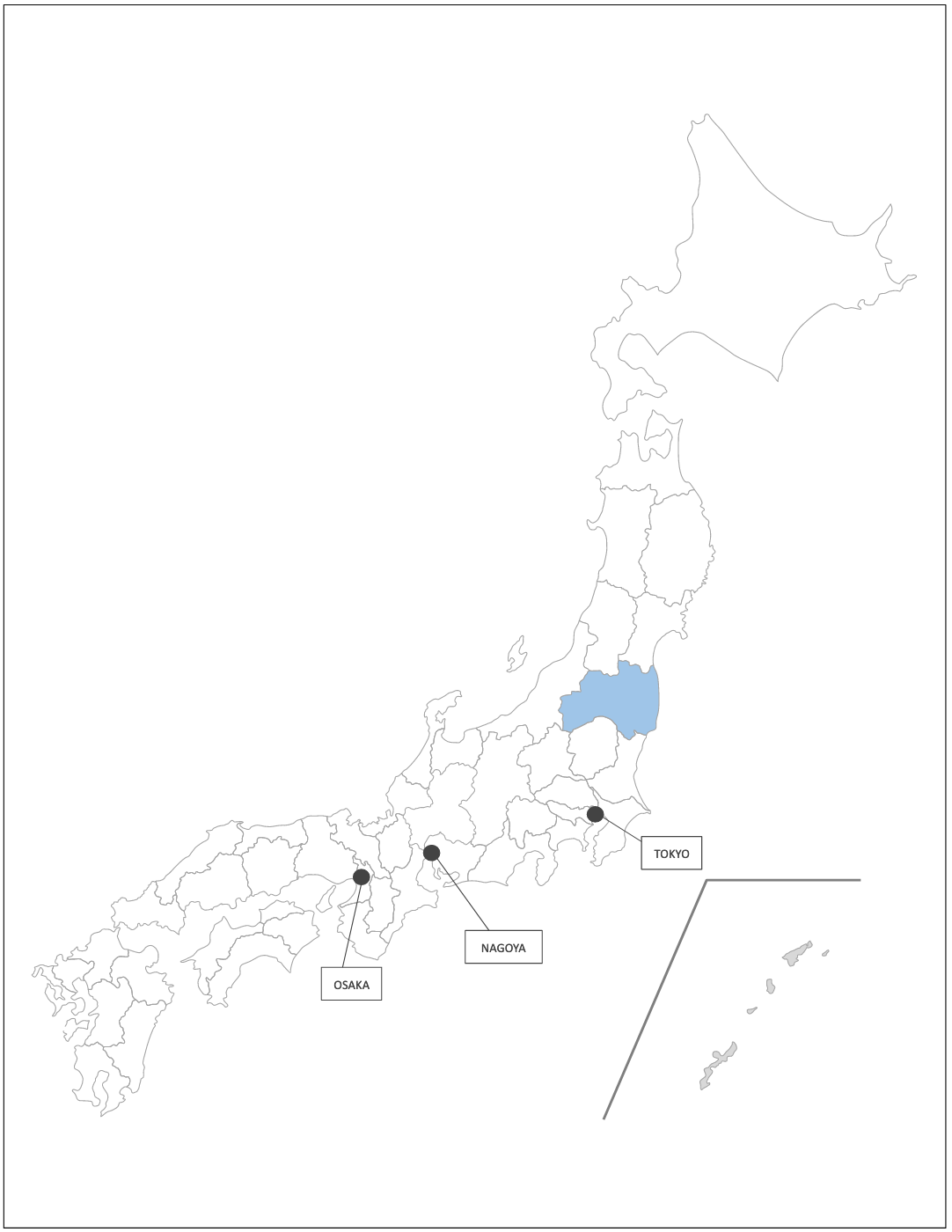

TOP 4 SAKE REGIONS IN JAPAN

You’ll find excellent sake in all regions of Japan, with no prefecture short on breweries. Indeed one of the great pleasures of traveling around the country is to enjoy the regional brews, especially when paired with regional cuisine. Just ask the locals for a recommendation and you’re sure to find a good one. Which region produces the overall best sake is of course subjective and opinions will vary greatly. However, when it comes to which regions produce the most, there’s no debate as it’s all just on the stats. These are Japan’s top four sake producing prefectures:

Niigata

Niigata lays claim to the largest number of breweries in Japan – said to be 89 in total – an ideal climate for producing some of the best sake in the country. The region is subject to a long, cold winter which aids with brewing and specifically, fermentation, while the abundant ‘soft’ water and renowned high-quality of local rice avail the key ingredients for producing the best sake. The waters off Niigata also bless the region with some of Japan’s best seafood, the perfect match of the local sake. It’s no surprise that Niigata also tops the charts when it comes to yearly sake consumption. Known for their crisp taste, Niigata sake are said to be gentle on the palate and with no lingering aftertaste.

Nagano

Our home region of Nagano lays claim to the second largest number of breweries – reported to be a total of 74 – and some of the best sake in Japan. It is one of only three prefectures – along with Yamanashi and Yamagata – to hold ‘Geographical Indication’ or ‘GI’ designation on both its sake and wine, testament to the quality and reputation of its products. Nagano’s long, cold winter and abundant water is ideal for producing top-quality sake, many of which use the snowmelt and natural springs to produce notably crisp tasting sake. Indeed water is key, as the production of 1 ‘bin’ (1.8L) of sake requires around twenty times more water. Nagano sake is said to be clean tasting and soft of the palate.

Hyogo

Unlike Niigata and Nagano that are located in the cold alpine region of Central Japan, Hyogo lies to the west and in terms of sake production, is made-up of five areas which distinct brewing histories. A total of 69 breweries are found in Hyogo, of which the Nadagogo area / tradition is the most celebrated. The area takes advantage of naturally-occurring mineral water that ensures a source of abundant, pure water in combination if with a locally-grown large grain rice ideal for sake production. Given the existence of distinct traditions of brewing within Hyogo, there is no one archetypal sake or taste profile to speak of in the region. But rest assured they are good and rank amoung the most reputed sake in Japan.

Fukushima

Returning north to the Tohoku region, Fukushima Prefecture is the fourth largest producer of sake in Japan, reported to have 63 operational breweries. Much like Niigata and Nagano, Fukushima is subject to a long, cold winter well-suited to brewing, with abundant clean water and high-quality rice. Fukushima also maintains distinct areas and traditions when it comes to sake production, each varying in taste but overall, the region’s sake is known for its ‘umami’-laden flavours while balancing a rich yet refreshing taste.

WINE & DINE IN NAGANO: BOOK A TOUR OR CHARTER

Based in Nagano and operating all year round, we are the region’s No.1-rated tour and charter operator. As a registered travel agent, we can arrange tours, transport, accommodation or combine them into a travel package that best suits your needs and interests. Want to visit one of Nagano’s best sake breweries, wineries or restaurants? We’ve got you covered! Our ‘Wine & Dine in Nagano: Book a Tour or Charter’ page is a great place to start when planning your visit to Japan’s sake and wine hotspot. We hope to see you soon in Nagano!

TERMINOLOGY YOU SHOULD KNOW

Dipping your toes into the warm world of sake is tremendously rewarding but can also be a little daunting. With so much to get your head around, we recommended starting with these useful terms:

Amakuchi: sweet taste.

Amazake: sweet, cloudy sake that is sometimes alcoholic and sometimes is not.

Dai-jingo: polishing rate of 50% or less with added distilled alcohol.

Futsushu: translates as ‘table sake’, typically non-premium, cheap and a good way to end-up with a hangover.

Genmai: unpolished rice.

Genshu: sake that has not be diluted with water during the brewery process leaving it with a notably higher alcohol content – typically 18 to 21%.

Ginjo: polishing rate of 60% or less (down to 51%) with added distilled alcohol and fermented at a low temperature.

Honjozo: polishing rate of 70% or less (down to 61%) with added distilled alcohol.

Jizake: locally-brewed, an equivalent of micro-brewed.

Junmai: pure sake made only from rice, water and koji.

Junmai-daijingo: polishing rate of 50% or less with added distilled alcohol with no added distilled alcohol – considered top-shelf.

Karakuchi: dry taste.

Koshu: aged sake, often identifiable by the colour they absorb from the barrels the sake is aged in, often with a subtle honey flavour.

Namazake: unpasteurised sake that contains live yeast cells and bacteria left-over from the brewing process. Must be refrigerated and is typically only available in winter or spring.

Nigorizake: unfiltered sake, typically cloudy with sediments of rice in the liquid.

Nihonshu: the general name for what most foreigners refer to as sake. The word ‘sake’ actually means ‘alcohol’ in Japan. All alcohol. So if you’re after what we call sake, you should actually being asking for nihonshu.

Sparkling sake: you guessed it = sparkling / carbonated sake.

Tokubetsu: signifies a special / limited brew and often precedes the term for polishing ratio i.e. ‘tokubetsu honjozo-shu’ or ‘tokubetsu junmai-shu’ = better / more expensive than the brewer’s standard honjozo or junmai.

Umami: considered the fifth taste group – in addition to sweet, bitter, salty and sour – you may have heard of ‘umami’ in relation to food however it also used to describe sake. Translating as ‘pleasant savoury taste’

JAPAN SAKE FAQs

Getting your head into and around sake can seem daunting at first. While it can take a lifetime to master, all journeys begin with those small, first steps and by asking questions, you’ll quickly learn it is actually quite accessible. With that in mind, here’s some of the most common early questions we hear from guests:

Is sake the same thing as ‘rice wine’?

Sake is sometimes referred to as rice wine in English. It plays a role similar to wine in Western culture, often paired with food, and uses a fermentation process to convert glucose to alcohol however the manner in which that occurs is quite different. Wine uses a single fermentation process in which yeast converts sugars that are already present in the grapes into alcohol, whereas sake requires what is referred to as a ‘multiple parallel fermentation that uses ‘koji’ a type of mold to first breakdown the starch in the rice grain into glucose (sugar) which in turn is then converted to alcohol by introduction of yeast into the process.

What percentage alcohol is sake?

After the initial brewing process, sake typically has an alcohol content of between 18% to 21%. Most sake is then diluted with water reducing the alcohol content to between 12% to 17%. There is sake, called ‘genshu’, that is not diluted using water and will therefore have higher content – at 18% to 21% – but most will range from 12% to 17%. As noted above, brewers must list the alcohol content on the bottle however it is not represented by a % symbol (which lists the percentage of rice) but instead, is marked as such: ‘アルコール15度’ = 15% alcohol content.

When is the best time to enjoy sake?

You can enjoy sake anytime of year. Most brewing occurs from December to February, meaning that mid to late-winter and spring is a great time to enjoy the year’s new sake, including ‘namazake’ (unpasteurised sake) which is available for only a limited amount of time, and joining a brewery tour. Spring is all about the cherry blossoms and enjoying the year’s new sake in combination with ‘hanami’ (flower-viewing), while summer brings festivals and fireworks and autumn leaves in months of October and November – all of which will be accompanied and enjoyed with sake. In short, the answer is there’s never a bad time to visit!

How is it served / consumed?

Sake is consumed in many ways. It can be enjoyed cold to cool – referred to as ‘hiya’ = 5-20 °C, at room temperature – referred to as ‘joun’ = 20-30 °C – or hot – referred to as ‘atsukan’= 30-55 °C. And this is just the tip of the iceberg. There are many subcategories and terminology that cover smaller temperature units, to an almost baffling point. Many sakes will come with a serving suggestion i.e. cold, hot or room temperature – and some brewers or bars can be quite militant about that aspect however speak to most brewers and they will tell you the serving suggestion is just that, a suggestion. You can consume sake in whichever way you most enjoy and in a range of drinking vessels including ‘choko’ – a small, circular ceramic cup, ‘masu’ – a square timber vessel, from a glass, or any combination of those. Sake is typically bottled in glass but you will also see it in ceramic and metal vessels, along with paper containers (but perhaps best to avoid these as it’s almost certainly cheap and nasty). When drinking sake with others in Japan, it is custom to pour each others drinks and not to pour your own. If you get this wrong don’t worry. Japanese realise it is not the custom in many other countries and won’t hold it against you, but if you can remember to join in, you’ll get a warm reception. Younger people should pour for their elders or in a work relationship, subordinates pour for their boss or manager before that person reciprocates with both parties usually make a big fuss and show of it, especially as more and more is consumed.

How can I make sure I choose a good one?

Much like most alcohol, the price will be a good indication quality. You don’t have to spend a fortune to find a good sake with many decent bottles available in-store for around JPY1200 to JPY1500. Once you hit the JPY3000 mark you should be enjoying a good sake and as you pass JPY5000 you’ll be enjoying some of the best – with prices going as high as you like. For many sake-drinkers, the ‘rice polishing rate’ is a good indication of a more refined sake, remembering that the lower % the more refined the taste (at least in theory). Sake milled to 50% and less is labelled ‘daijingo’ while ‘junmai’ indicates that no distilled alcohol has been added during the process i.e. many consider these cleaner and better to drink. When you combine those two terms, ‘junmai daijingo’ is considered by many as the top end of the spectrum. A good term to remember when scanning a store shelf or restaurant menu for a good sake.

I’d like to visit a sake brewery. Can you arrange that?

Yes. Based in Nagano we are surrounded by breweries and can arrange private tours including a guided tasting at a brewery or just transport to and from the destination of your choice. See our ‘Wine & Dine in Nagano: Book a Tour or Charter’ page for details.

When is the best time to visit a brewery?

We operate all-year-round and can arrange tours and transport in all seasons. If you want to see the brewing process, it’s best to visit between December to February when new sake is being processed however many breweries will provide tours at all times of year and almost all will provide tastings through all seasons.

Can I buy sake through your website?

We’re working on that but for the time being, it is not possible to purchase sake through our website. But keep checking as it’s something we’re working on!

What is the legal drinking age in Japan?

To consume alcohol in Japan, you must be at least 20 years of age. Restaurants, bars and stores strictly enforce the law as they face severe repercussions should they serve someone under age.