Japanese garden design is a centuries-old art form that reflects the cultural values, religious beliefs, and aesthetic principles of Japan. But not all Japanese gardens are created equal. Over time, several distinct styles have evolved, with each serving unique purposes and embodying different philosophical or practical ideals.

In this article, we’ll explore the eight unique garden types you’ll encounter across Japan, and explain the details that make each garden type distinct so you can enjoy your time exploring Kyoto’s mossy temple courtyards and the grand estates of Edo-period daimyo to the fullest.

1. Heian Estate Garden (Shinden-zukuri Gardens)

Originating during the Heian period (794–1185), these gardens formed the elegant entertainment space of aristocratic estates. The gardens were designed to be seen from the shaded veranda of the main building and were typically on the opposite side of a pond. Bridges arched over water, connecting small rocky islands. Many of these gardens would contain a cherry tree, to symbolize the feminine yin, and a citrus or pine tree, to represent the masculine yang.

Heian courtyards were not planted heavily. Instead, they served as venues for events like archery, poetry contests, dances, and seasonal festivals. On festival days, noble guests would relax in tents, watch children perform dances, or enjoy viewing the cherry blossoms in full bloom. Garden ponds often hosted elegant boating excursions. Musicians played aboard carved dragon-headed boats (ryūtōbune) or fowl-shaped vessels (gekisubune) that glided across the water.

Recommended Gardens

While no true Heian-period estate gardens remain intact today, several gardens throughout Japan still preserve the essence, design philosophy, and atmosphere of these classical landscapes. For those interested in viewing Heian-era gardens, we recommend the following two destinations.

Katsura Imperial Villa (桂離宮)

Located in the western suburbs of Kyoto, the Katsura Imperial Villa is a masterwork of Japanese garden design that draws direct inspiration from the aesthetics and literature of the Heian period. Though built in the early Edo period by Prince Hachijō Toshihito (1579–1629), its design is a homage to the iconic Heian-era book, The Tale of Genji.

Toshihito, a devout admirer of classical poetry and prose, selected the site along the Katsura River due to its poetic significance in The Tale of Genji. Over time, Toshihito and his son transformed the modest home and garden into a sophisticated villa surrounded by a central pond, just like the gardens from his favorite book.

Shinsen-en (神泉苑)

For a more direct connection to the original Heian capital, Shinsen-en Garden, just south of Nijo Castle, holds special historical significance. Originally part of Emperor Kammu’s palace complex when Kyoto was first established as Heian-kyō in 794, this site served as an official pleasure garden where aristocrats would hold moon-viewing parties, boat across the pond, and perform poetry readings.

Though only a fraction of its original 33-acre size remains, Shinsen-en still retains the core features of its Heian-era layout. The central Hojuju-ike pond, a small island shrine to the Dragon Queen, and the iconic curving vermillion bridge evoke the atmosphere of ancient courtly leisure. The presence of shrines to Benten and Inari, along with the image of Kobo Daishi in the main hall, highlight the site’s transformation over the centuries into a spiritual as well as aesthetic space.

2. Paradise Garden (Jōdo-teien)

As Buddhism gained popularity among the aristocracy, a new type of garden emerged: the Pure Land Paradise Garden. These began appearing in the late Heian period and reflected the belief in Amida Buddha’s Western Paradise. The gardens were symbolic, often designed around a large central pond that represented the lotus pond of rebirth. A middle island (nakajima) stood in the water, connected to the shore by bridges, which signified the crossing to salvation.

These gardens were a reaction to the belief that the world had entered the age of mappō, a degenerate era when enlightenment was nearly impossible. Creating a garden in the image of paradise was a way to earn spiritual merit and bring peace to a troubled age.

Recommended Garden

Byōdō-in (平等院)

The most famous example of a Pure Land Paradise Garden is Byōdō-in in Uji, near Kyoto. Originally built in 998 as a villa for Fujiwara no Yorimichi, it was converted into a Buddhist temple in 1052. The Phoenix Hall faces a wide pond, with a large statue of Amida seated inside. Viewers sat on the eastern bank and gazed westward across the water, imagining their rebirth into paradise.

3. Rock Garden (Karesansui)

If you visit Ryōan-ji in Kyoto, you’ll encounter a garden without water, flowers, or trees. Instead, you’ll see fifteen rocks arranged carefully in a bed of white gravel. This is a karesansui, or a dry landscape garden. Though rooted in Shinto practices of rock worship, the style reached its full form in the Muromachi period, influenced strongly by Zen Buddhism.

Earlier rock gardens were sometimes just parts of larger estate gardens. But by the 15th century, temples began designing entire gardens in this minimalist style. The raked gravel represents flowing water, while the stones stand in for mountains or islands. Every element has been reduced to its most essential form.

The art of raking is not merely for aesthetics. Monks rake the gravel as a form of meditation. Creating straight lines or intricate curves requires full concentration and quiets the mind. Rain or wind erases the patterns, but this impermanence is part of the beauty. Dry gardens also endure better than water gardens. They are not affected by droughts, floods, or even earthquakes in the same way.

Recommended Garden

Taisan-ji An’yō-in (太山寺 安養院)

Located in Kobe, An’yō-in offers a distinctive style of karesansui. Unlike the more familiar flat sand gardens like the one at Ryōan-ji, the An’yō-in rock garden, constructed during the Azuchi-Momoyama period, embraces a kare-ike (dry pond) style that emphasizes bold rock groupings rather than raked gravel.

4. Meditation Garden (Kanshō-niwa or Zakan-shiki-teien)

Meditation gardens are designed to be looked at, not entered. They are often viewed from a seated position inside a temple or along a veranda. These gardens are known as kanshō-niwa or zakan-shiki-teien, which literally means "gardens for viewing while seated."

During the Muromachi period, garden designers began drawing inspiration from Chinese ink paintings. Many of these gardens include ponds, islands, and rocks arranged like scenes from scroll art. The composition creates depth and contrast, much like a painting done in ink and wash. These gardens offer stillness and encourage reflection, inviting you to “travel” through the landscape with your eyes.

Recommended Garden

Kyōrinbō (教林坊)

Founded in 605 by Prince Shōtoku, Kyōrinbō in Shiga Prefecture near Omi Hachiman is a deeply spiritual site known as the "Temple of Stones". The temple takes its name from a legend in which Prince Shōtoku taught while seated in a forest, hence the name "Kyōrin", meaning "teaching in the grove." A large boulder known as "Taishi no Seppō Iwa" (Prince’s Preaching Rock) still stands in the temple grounds, marking this origin story and forming part of its scenery.

At the heart of Kyōrinbō is its meditation garden, designed by the famed garden designer and tea master Kobori Enshū. With subtle rock groupings and a natural sense of balance, this garden is a textbook example of zakan-shiki-teien: a place to sit, observe, and enter into meditative calm.

Kyōrinbō is only open to the public during the cherry blossom and autumn leaves seasons.

5. Tea Garden (Roji)

If you ever have the chance to take part in a Japanese tea ceremony, pay close attention to the path leading to the teahouse. This is the roji, or “dewy ground” garden, which marks the transition from the outer world to the quiet interior of the tea room. Developed during the 15th and 16th centuries, these tea gardens reflect the philosophy of wabi—beauty in the rustic and imperfections.

Sen no Rikyū, the Edo era’s most influential tea master, along with his students including Uraku—brother of Oda Nobunaga (the first of Japan’s great unifiers), emphasized rustic materials and subdued colors. Tea gardens followed this philosophy. You’ll find stepping stones leading to the chashitsu (teahouse), bamboo fences, moss, and evergreen shrubs. Bright flowers and flashy features are avoided. Even the cushion in the waiting arbor is a quiet red, offering the only splash of color.

The garden prepares the guest mentally. Walking the winding path slows the pace and clears the mind. Ponds and rock arrangements are left out intentionally to avoid distraction. The garden simulates a mountain hermitage, drawing the visitor away from city life and into a world of stillness.

Recommended Garden

Urakuen (有楽苑)

Located in Inuyama, just outside of Nagoya, Urakuen is one of Japan’s most important tea gardens and home to Jo-an, a National Treasure and one of the finest surviving tea houses from the early Edo period.

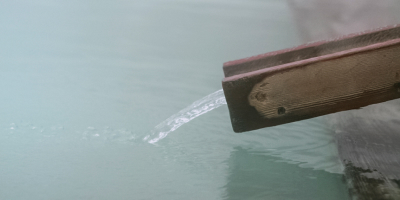

Urakuen’s garden is a textbook example of roji design, with a clear progression from outer garden (soto-roji) to inner garden (uchi-roji). Each element, from the stone lanterns, waiting benches (koshikake), stepping stones (tobi-ishi), and water basins (tsukubai), serves to slow the pace of movement and shift the guest’s mindset away from everyday concerns.

Recommended Tour: Embark on a captivating tour from Nagoya to explore the oldest castle in Japan, a National Treasure teahouse, a "city of swords," and the charms of Central Japan on Snow Monkey Resort's Private Tour from Nagoya: Samurai Swords and Japan's Oldest Castle.

Learn about the craftsmanship involved in creating a samurai sword, meet a bladesmith and learn how to properly sharpen a kitchen knife, and stroll along the streets of Inuyama where you can indulge a wide array of street food under the shadow of Japan's oldest original castle.

6. Courtyard Garden (Tsuboniwa)

Hidden between the walls of townhouses or tucked under deep eaves, tsuboniwa are miniature gardens designed for enclosed spaces. The name comes from tsubo, which originally referred to a unit of measure roughly equivalent to two tatami mats. Most tsuboniwa are no more than a few square meters, but they manage to distill the essence of nature into that tiny space.

These gardens often receive little direct sunlight and rely on shiny, dark-green plants, mosses, and moisture-loving species. You may find polished stepping stones, a small lantern, or a single ornamental tree. They are places of quiet escape, often placed next to a tatami room or bathroom to provide a calming view.

In traditional belief, a tsuboniwa serves as a point of energy circulation in the home, similar to acupressure points on the body. They enhance airflow, humidity, and atmosphere in the house while providing a moment of serenity in daily life.

Recommended Garden

Tsuboniwa by nature are located mainly in private residences, restaurants, hotels, and businesses. The Nagoya Culture Path is lined with well-preserved estates, once home to wealthy merchants, journalists, missionaries, and cultural figures of the Meiji through early Showa Eras (1868–1930). Many of these houses have beautiful courtyard gardens to view as you explore the estate.

Recommended Tour: Snow Monkey Resort's 1-Day Guided Garden Walk through Nagoya's Castle, Gardens, and Historic Estates will take you into several historical estates and private gardens of Nagoya's titans of industry. Marvel at the gilded artwork and golden screens in Honmaru Palace and sip tea while gazing at a garden designed for a daimyo as you are led by an experienced, English-speaking guide through Nagoya on this full-day tour.

7. Stroll Garden (Kaiyū-shiki-teien)

Among the largest and most visually striking gardens in Japan are the kaiyū-shiki-teien, or stroll gardens. These were especially popular during the Edo period, when daimyo lords were required to maintain estates in both the capital (Edo) and their home provinces. Their gardens became statements of power, taste, and cultural knowledge.

A stroll garden is meant to be walked. Paths wind through artificial hills, over bridges, past waterfalls, and around large ponds with islands. Designers arranged scenes to appear in a particular sequence, hiding and revealing views with each turn—a technique called miegakure.

Famous stroll gardens like Kenroku-en in Kanazawa, Kōraku-en in Okayama, and Kairaku-en in Ibaraki (Three Great Gardens of Japan) contain a blend of influences. You’ll see elements borrowed from Heian estate gardens, such as large boating ponds, as well as Zen-inspired viewpoints, tea huts, and even agricultural motifs like rice fields and orchards. These gardens are both elegant and interactive, encouraging the visitor to explore slowly and appreciate every change in perspective.

Recommended Garden

Besides the Three Great Gardens of Japan, Kenroku-en, Kōraku-en, and Kairaku-en, there are many other beautiful examples of stroll gardens across the country.

Tokugawa Garden (徳川園)

Located in Nagoya, Tokugawa Garden (Tokugawa-en) is a classic Edo-period stroll garden originally created as the retirement villa for the Owari branch of the Tokugawa family, one of the most powerful branches of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Symbolism is deeply embedded in the design: the pond represents the ocean, and the surrounding rocks and bridges form a miniature landscape of Japan. Towering black pines, weeping willows, and seasonal flowers add drama and softness throughout the year. This garden once reflected the wealth and sophistication of a daimyo lord, and it still impresses visitors today.

Recommended Tour: Snow Monkey Resort's 1-Day Guided Garden Walk through Nagoya's Castle, Gardens, and Historic Estates will take you into several historical estates and private gardens of Nagoya's titans of industry. Marvel at the gilded artwork and golden screens in Honmaru Palace and sip tea while gazing at a garden designed for a daimyo as you are led by an experienced, English-speaking guide through Nagoya on this full-day tour.

Genkyū-en (玄宮園) – Hidden Beauty Beneath Hikone Castle

Nestled at the foot of Hikone Castle in Shiga Prefecture, Genkyū-en Garden is a stunning example of an Edo-period kaiyū-shiki-teien. Constructed in 1677 by Ii Naooki, the fourth lord of the Hikone domain, the garden was inspired by classical Chinese landscape aesthetics, particularly those of the Eight Views of the Xiaoxiang region.

The central pond is studded with islands and arched bridges, surrounded by meandering paths that lead past teahouses, pavilions, and groves of pine and maple. One of the most captivating features of Genkyū-en is the use of borrowed scenery (shakkei), incorporating the towering Hikone Castle into the background.

8. Hermitage Garden (Rikyū Garden)

Last, we come to the most personal of Japan’s garden styles: the hermitage garden. These were designed by samurai and scholars who had retired from public life during the Edo period. Built in mountain villages or quiet city corners, hermitage gardens were places for reflection, poetry, and tea.

Paths leading to the garden were often narrow and winding, with frequent corners to slow the visitor’s pace. This meandering approach was meant to calm the mind before reaching the garden itself. Inside, you might find a tea hut, a dry landscape composition, or a borrowed view of distant hills. Unlike grand estate gardens, these spaces feel intimate and enclosed.

Recommended Garden

Shisendō (詩仙堂)

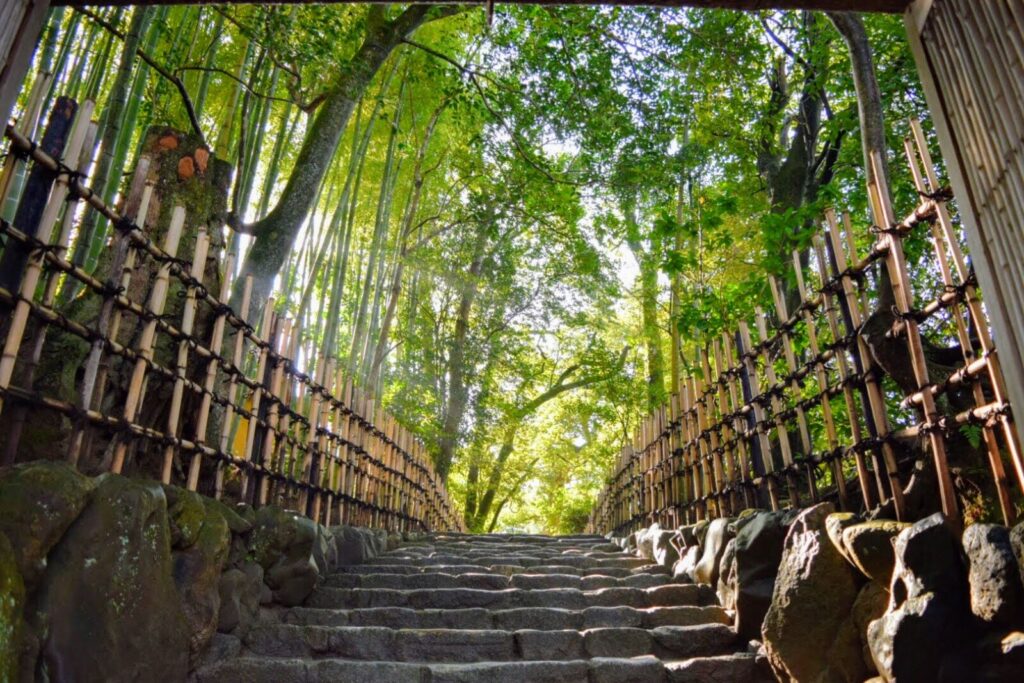

Located in the quiet northern hills of Kyoto, Shisendō was built in 1641 by Ishikawa Jōzan, a retired samurai turned Confucian scholar and poet. After a life in politics and warfare, Jōzan sought solitude, literature, and harmony with nature, so he created a retreat that embodied all three.

The garden at Shisendō is a hermit’s ideal garden: intimate, tranquil, and designed for sitting still and listening. The central feature is the courtyard framed by bamboo groves, azaleas, and clipped shrubs. From the open tatami room of the main hall, visitors can sit and gaze upon the garden, just as Jōzan did while composing poetry.